Back from a month in Sardegna and the magical land that is the village of Santu Lussurgiu, I am thinking this morning about voice, and about how my own voice becomes an instrument of knowing, both of the musico-cultural context around me and also of myself and how I unconsciously shift performance styles from one context to another. In Sardegna, voice—and how people hear voice—becomes a beautiful entry point into how Americanness is heard, how “country” and the wild west is heard; through this usage of my own voice in performance settings, I am able to learn about how Sardi, in the end, view their own music and their own voices.

Last summer, while performing a solo show at a music venue called Abetone in Sassari (on the northern part of the island), a well-known jazz musician came up and told me that I remind him of Joan Baez, a performer who toured extensively in Italy. This is a comment I have fielded repeatedly in Sardegna, and which fascinates me, as I never really listened to Joan Baez and so don’t feel influenced by her in the least. And it’s also very specific. When I pushed him to explain a bit more, he described how, even when I’m singing Guccini’s famous “Il Vecchio e Il Bambino” in Italian, I modulate my voice and manipulate the chest/head voice transitional space in an “American” way that reminds him of Baez, especially in the head range. When I queried whether this was influenced by an American-inflected diction when singing in Italian, he insisted that it wasn’t about pronunciation, it’s about singing style. So, to this musician, even when I’m singing in Italian, I sound iconically American.

Last summer, while performing a solo show at a music venue called Abetone in Sassari (on the northern part of the island), a well-known jazz musician came up and told me that I remind him of Joan Baez, a performer who toured extensively in Italy. This is a comment I have fielded repeatedly in Sardegna, and which fascinates me, as I never really listened to Joan Baez and so don’t feel influenced by her in the least. And it’s also very specific. When I pushed him to explain a bit more, he described how, even when I’m singing Guccini’s famous “Il Vecchio e Il Bambino” in Italian, I modulate my voice and manipulate the chest/head voice transitional space in an “American” way that reminds him of Baez, especially in the head range. When I queried whether this was influenced by an American-inflected diction when singing in Italian, he insisted that it wasn’t about pronunciation, it’s about singing style. So, to this musician, even when I’m singing in Italian, I sound iconically American.

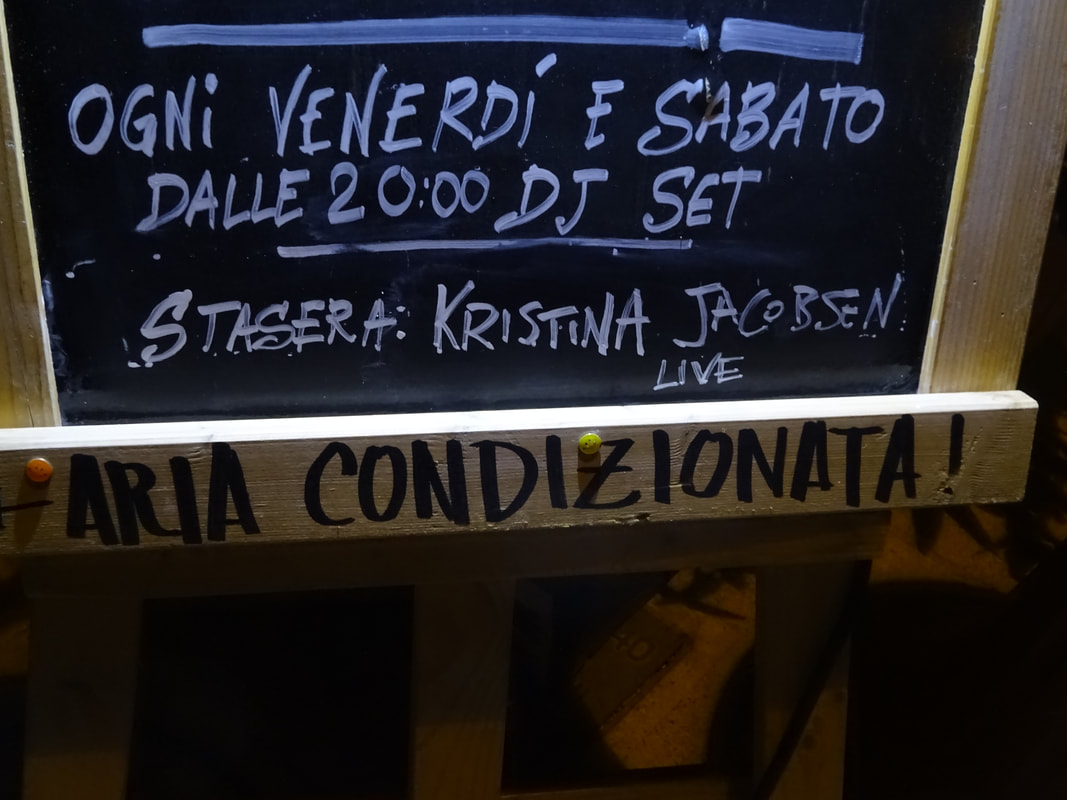

Abetone Music Bar, Sassari, Italy.

Abetone Music Bar, Sassari, Italy. More recently, on my recent trip back to Sassari to play a show a few weeks ago, I had lunch with dear friends, who speak excellent British English in addition to Italian (and also some Sardo). As a result, when we meet, we typically code switch back and forth between English and Italian, as needed and to fit the topic of the conversation, our knowledge of vocabulary in different languages, etc. It’s a wonderful and fluid thing, this ability to switch back and forth with close friends. In the middle of one of these switches, my friend Nike stops me and says, “You sound completely different when you’re speaking in English and when you speak Italian.” I was flummoxed. She went on to describe how my pitch, intonation and body language seem to shift as I traverse the zones between these two languages, one Germanic and one Romantic. As I think about this now, however, it begins to make sense. As is true for so many who travel, we inhabit different identities when we speak—and are inhabited by—different languages. And we are able to express different parts of ourselves. I recall the second night I was in Sardegna, on my very first trip there three years ago, when I dreamt in Italian, and realized that I had important musical and psychological work to do in this place, on this soil and on this sheepherding island, so far away from Navajo Nation and yet with so many uncanny resonances. Language, and the possibility of language, opens us up to other, sometimes freer, selves, giving us permission to grow and stretch, vocally and psychologically, in ways we might not feel were possible without the expressive vehicle languages give us.

And yet, despite these shifts in expressive resources, there is something in us that remains grounded and constant, a pure expression of self, regardless of the language in which we sing. In a final solo performance in the southern city of Cágliari at Covo Art Café, a Canadian expat, musician and Cágliaritano (resident of Cágliari) came up to me after the show and told me he loved all the languages I had sung in (in this case Italian, Sardo, Norwegian, Navajo, English) and particularly how my singing style had changed as I sung an original folk song in Norwegian. But after this, he told me: “During the show, I asked myself: do these people [Italian speakers/listeners] understand what she is saying, even though she is singing in English”? Then, when you started singing in Italian, and then Norwegian, I realized they did! Because there was a through-line, something consistent about your stage presence, your persona, your being as your performed, that was coming through in each language you performed in.” So, languages are vehicles for different expressions of self—expressed both in the words we use to sing our song, but also the range, intonation and singing styles we use to express ourselves in each of these languages—but they are unified and cohere through the singular body we inhabit and the sense of self that we share with others, in any language.

And yet, despite these shifts in expressive resources, there is something in us that remains grounded and constant, a pure expression of self, regardless of the language in which we sing. In a final solo performance in the southern city of Cágliari at Covo Art Café, a Canadian expat, musician and Cágliaritano (resident of Cágliari) came up to me after the show and told me he loved all the languages I had sung in (in this case Italian, Sardo, Norwegian, Navajo, English) and particularly how my singing style had changed as I sung an original folk song in Norwegian. But after this, he told me: “During the show, I asked myself: do these people [Italian speakers/listeners] understand what she is saying, even though she is singing in English”? Then, when you started singing in Italian, and then Norwegian, I realized they did! Because there was a through-line, something consistent about your stage presence, your persona, your being as your performed, that was coming through in each language you performed in.” So, languages are vehicles for different expressions of self—expressed both in the words we use to sing our song, but also the range, intonation and singing styles we use to express ourselves in each of these languages—but they are unified and cohere through the singular body we inhabit and the sense of self that we share with others, in any language.

After twenty years of living on the Navajo Nation, I allowed myself to leave and explore other communities in which to do ethnographic research, and ended up, half way around the world, on a matriarchal island of sheepherders, horse-lovers, artists and craftspeople, also colonized by the Spaniards, who also eat mutton as a specialty food, and also excel in jewelry making using turquoise and red corral as central foci. How is this possible? I think we gravitate toward similar thematics, but also toward certain environments—in my case, rural, family-centered, face-to-face, with complex language politics and strong, feisty women—perhaps because these are things that resonate—and have always resonated—with me, personally. These are the places where my soul feels at ease, and where I feel broad, expansive, and able to express, perhaps, a more fully formed, well-rounded, earthy and joyous portion of myself, in community with others. Ahéhee’, Mille Grazie, Navajo Nation and Sardegna, for giving me those parts of myself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed