After more than two years away, on Friday, I was finally able to return to one of my favorite spots on Navajo Nation, the Window Rock Flea Market. Parking my truck in the dusty parking lot, I beelined to the food stands with my dog, Nira, I decided on the Grilled Food Café, where I ordered my favorite Diné (Navajo) dish of all time, “steam corn mutton stew,” also known as neeshjízhii. At the risk of unduly singling out any one vendor—all the vendors I have eaten at, there, and across Navajo Nation, also make delicious neeshjízhii, squash stew, and breakfast burritos with thick, homemade tortillas—I wanted to do a shoutout to this food stand in particular because they have just opened back up after the pandemic and because the proprietors are so explicit and intentional about the local value and craft of the food they make and sell.

Neeshjízhii is a Diné specialty food, and it is incredibly labor intensive to make. The corn, also called neeshjízhii, is smoky and complex, and has a slight hint of caramel after you bite into it (it’s similar to “chicos” in a New Mexican context). Making it takes several days, including harvesting the ears, steaming them on the cob in an earthen pit on cedar wood coals, shucking and drying the ears, and then removing the kernels from the cobs (southwest farmfresh.org). The corn is served in a simple broth with large chunks of mutton (dibé bitsį’ or sheep meat) on the bone, with salt as the only additional seasoning. It’s a deceptively simple meal, but don’t be fooled: paired with the grease and crunch of the frybread that comes on the side, it’s one of the most satisfying meals I’ve ever eaten (my friend refers to this stew as “Diné chapstick,” because it makes your lips greasy and shiny).

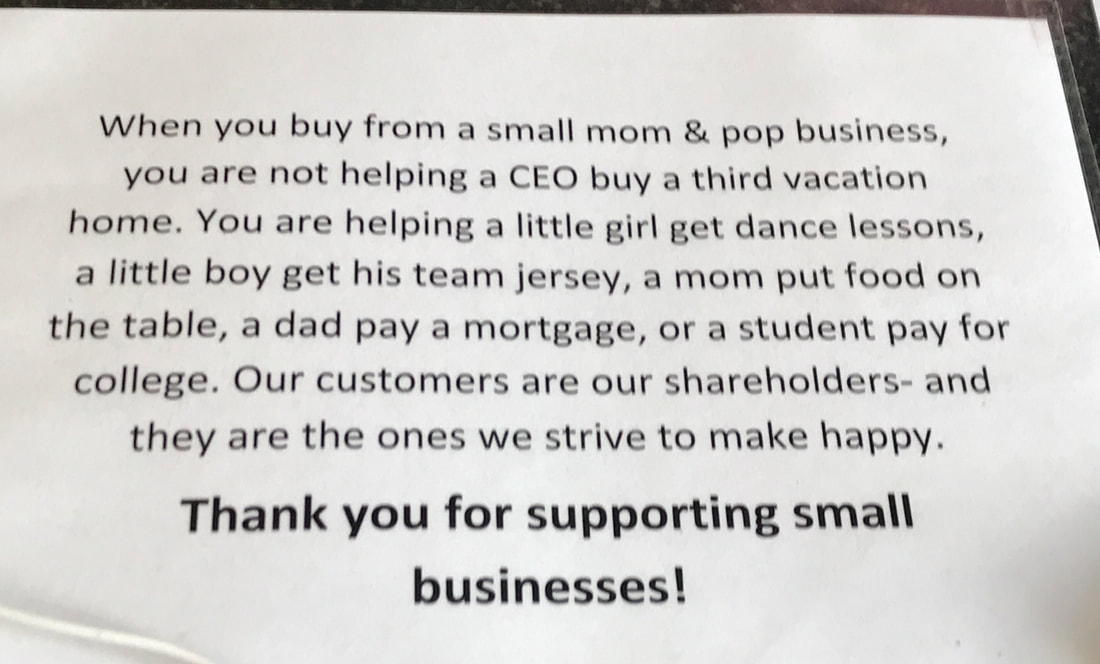

The sign in the window of the Grilled Food Café reads:

“When you buy from a small mom & pop business, you are not helping a CEO buy a third vacation home. You are helping a little girl get dance lessons, a little boy get his team jersey, a mom put food on the table, a dad pay a mortgage, or a student pay for college. Our customers are our shareholders, and they are the ones we strive to make happy. Thank you for supporting small businesses!”

Neeshjízhii is a Diné specialty food, and it is incredibly labor intensive to make. The corn, also called neeshjízhii, is smoky and complex, and has a slight hint of caramel after you bite into it (it’s similar to “chicos” in a New Mexican context). Making it takes several days, including harvesting the ears, steaming them on the cob in an earthen pit on cedar wood coals, shucking and drying the ears, and then removing the kernels from the cobs (southwest farmfresh.org). The corn is served in a simple broth with large chunks of mutton (dibé bitsį’ or sheep meat) on the bone, with salt as the only additional seasoning. It’s a deceptively simple meal, but don’t be fooled: paired with the grease and crunch of the frybread that comes on the side, it’s one of the most satisfying meals I’ve ever eaten (my friend refers to this stew as “Diné chapstick,” because it makes your lips greasy and shiny).

The sign in the window of the Grilled Food Café reads:

“When you buy from a small mom & pop business, you are not helping a CEO buy a third vacation home. You are helping a little girl get dance lessons, a little boy get his team jersey, a mom put food on the table, a dad pay a mortgage, or a student pay for college. Our customers are our shareholders, and they are the ones we strive to make happy. Thank you for supporting small businesses!”

After I finished my meal, I wandered around to the other vendors, leaving with a couple small gifts for friends and some new (to me) Diné gospel CDs from a vendor who loves Diné gospel and country western bands. I chatted with George, a dapper 81 year old who bikes into “town” each day to check his mail and who worked for many years harvesting sugar beets on a farm in Idaho, before moving back home. I gassed up at Navajo Petroleum, bought a Navajo Times (the weekly paper for the Navajo Nation, out on Thursdays) with the front page featuring a performer from the most recent Navajo Pride parade, and headed back to Albuquerque, hands smelling faintly of mutton, accompanied by the songs of gospel singer Larry Kaibetoney on the stereo.

A bowl of neeshjízhii with frybread or tortilla (your choice) will set you back between $11.00-$12.00, or about ½ the price of a high end entrée at your favorite restaurant. But the richness of the flavor, the sensory experience and the stories that come with it are priceless. Wherever you are, please consider supporting unique, local and artisanal food trucks and foodways.

NB: If you make the trip, please know that masking and social distancing are still fully in effect, per Navajo Tribal Law, on the Navajo Nation. Most food stands, and other flea market vendors, prefer cash, only.

A bowl of neeshjízhii with frybread or tortilla (your choice) will set you back between $11.00-$12.00, or about ½ the price of a high end entrée at your favorite restaurant. But the richness of the flavor, the sensory experience and the stories that come with it are priceless. Wherever you are, please consider supporting unique, local and artisanal food trucks and foodways.

NB: If you make the trip, please know that masking and social distancing are still fully in effect, per Navajo Tribal Law, on the Navajo Nation. Most food stands, and other flea market vendors, prefer cash, only.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed