Click to set custom HTML

|

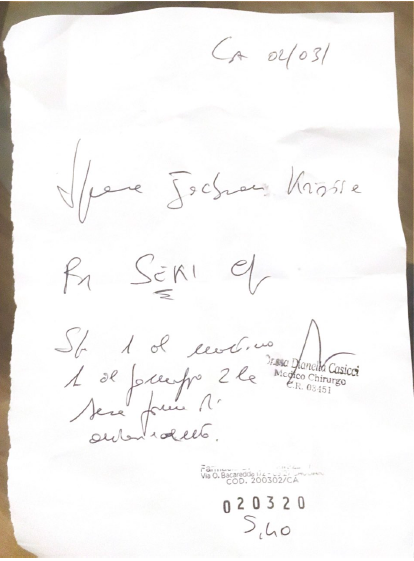

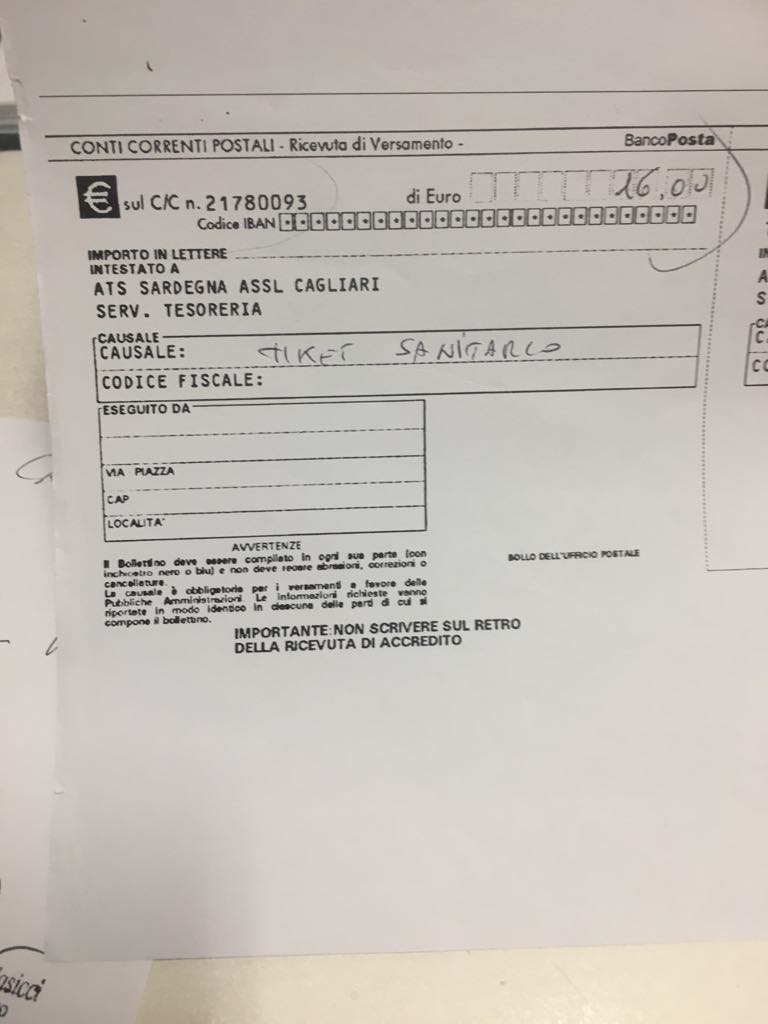

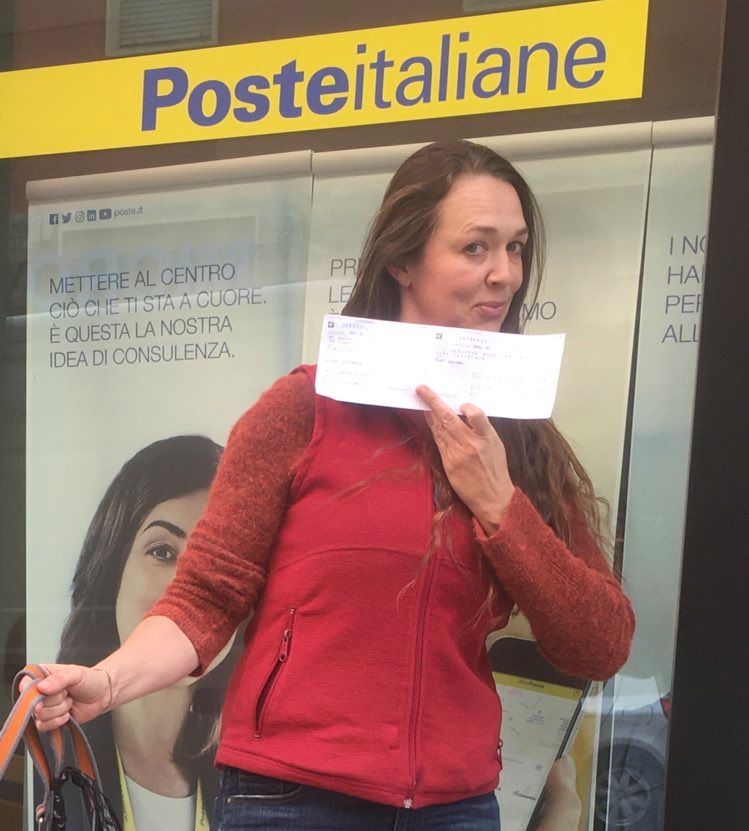

Over the weekend I developed a high fever due to a gas leak in my house. Worried about getting better as quickly as possible for a Northern Italian tour I was about to undertake (now sadly postponed due to the Corona Virus outbreak but taking place in January 2021), I went with a friend to the “Guardia Medica” in Cagliari. This is a public service that’s offered to Italian citizens and tourists for health issues that aren’t life threatening, and thus don’t warrant an emergency room visit. We arrived around 8:00 pm, when the clinic opens for its night-time hours (it opens when normal doctor’s hours end), at a large three-story house, with a broken metal gate. We press the buzzer to be allowed in, but there’s no response. Five minutes later, we are issued in, the first patients of the evening for our blonde-haired, fifty-something doctor. I recognize quickly that doctor-patient protocol and privacy are quite different, here. We have most of our conversation in what looks like a small office—I don’t realize until later that it’s also the examining room—with the door wide open, as people shuffle in to get in line after us. When she finds out I’ve recently returned from the United Arab Emirates, she exits the room and returns with a face mask on, confiding in us that this is the first time she’s worn it to see a patient. I tell her I am honored—I’m not quite sure how else to respond to her confession—and she raises my T-Shirt and proceeds to palpate my back and chest with her stethoscope, asking me to pant quickly in and out, “come un cane” (like a dog), for around 60 seconds, as my friend looks on in amusement and I do my best not to start giggling. She has me open my mouth and lower my tongue. Assured it’s not Corona Virus, she asks for my “tessera sanitaria” (a sort of Italian social security card), proscribes me a cough suppressant called “Seki” on a torn piece of white paper (the printer is jammed), writes the word “tiket sanitario” (health ticket) and the day and month but no year. She is wearing a white coat, but there is no medical equipment in the room that I can see beyond the stethoscope: no sink, no rubber gloves, no computer, and the entire exam is done with me seated on the metal chair I sat on when I entered. She then proceeds to the topic du jour, immigration, noting that the United States has just closed its doors to flights from China, South Korea, and now Italy. My friend, eager to balance the playing field on my behalf, notes that Italy has long closed its doors to many migrants themselves, including the many boats of North African migrants who have been refused a port of entry on Italian waters in recent months. The doctor then responds, “and look where our open border policies have gotten us now,” giving a knowing nod and a wary eye roll to indicate she’s talking about Corona Virus. My friend counters that, in fact, none of the known cases of Corona Virus have come from “l’Africa” and that, on the contrary, they are mostly from wealthier Italians who have the means to travel abroad and then carried inadvertently carried the virus home with them. The conversation continues, both firm in their positions, smiling brightly, and neither willing to cede. I am a bit dumbfounded, and my head is spinning. What has just happened, and is the person we saw actually a doctor? Since they didn’t take my temperature, can they really know I’m well? Is the torn piece of paper really a prescription, and is that seen as legitimate by a licensed pharmacist? Is it typical protocol to talk to a patient with an open door and then to discuss immigration policy and politics? On the flip side, is it possible that one can actually get seen and diagnosed, so quickly without an appointment and with such efficiency, despite the obvious lack of infrastructure and resources? And how could an entire appointment, not logged into any computer system I could see, only cost 16.00 €, and a prescription only 5.40 €, given to a foreign national using no insurance in this case? What I loved about this experience was its imperfectness, its lack of tidiness, its messiness. What I also loved was that, despite that, and the old building, and the gate that didn’t work, and the exam rooms that look like an old library from the 1950s, someone was willing to see me, treat me, and offer a bit of medical advice, and that they had no qualms about offering me other sorts of opinions on politics, as well. The latter, of course, is a very Italian thing—I am offered strongly opined unsolicited advice almost every day I live on Sardinian (also arguably Italian) soil—but in a funny way this is also oddly humanizing. I know where she stands, she knows where I and my friend stand, she wasn’t worried about a medical malpractice suit if she expressed her opinions or offered me somewhat haphazard care; that’s the space she was in at at 8:10 yesterday evening, and that’s what she had to offer me, her first patient of the evening. I have now, with the help of my friend, gone down the bureaucratic road of paying my 16.00 € (about a two hour process), and, in the meantime, will enjoy a good dose of vitamin C through one of my favorite local sources, Italian blood orange juice (amazing). Buona giornata, tutti, e buon proseguimento. Thanks to Giulia Biggio and Enrico Spanu for their splendid care of me in these past couple days, and for Giulia’s comments on this post.*

|

Author

Cultural Anthropologist, Singer-Songwriter and multilingual speaker Kristina Jacobsen blogs on the boundaries and connections between songwriting, ethnography and the songwriting life. Archives

September 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed