Nira Jacobsen, chocolate-colored Labrador Retriever, arrived in Sardegna on a steamy, humid day last September, via Los Angeles and Frankfurt, to Rome, where were took a ferry to Sardegna and where she accompanied me on my year of fieldwork here on the island, singing and writing songs, learning the Sardinian language, and generally taking part in the comings and goings of life, here.

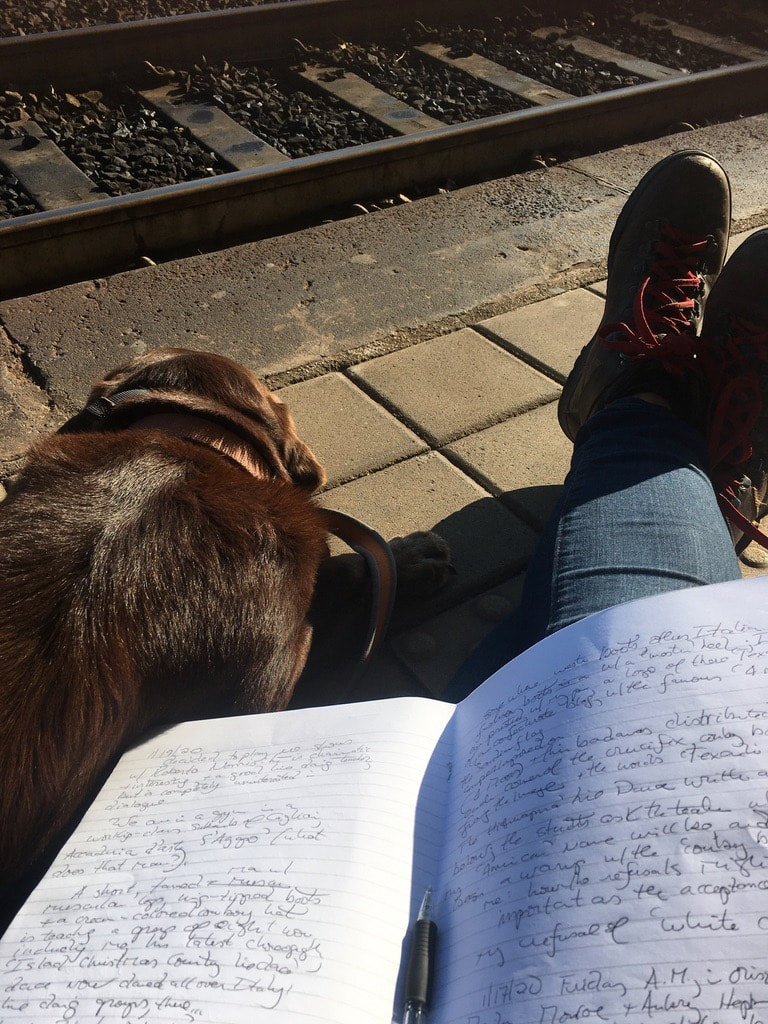

Since then, we have been inseparable, and, although not part of the initial plan to have her here with me for the year, doing fieldwork with her in my midst has been much like the narratives I’ve read of doing fieldwork with a child in tow. Each Sunday, we’ve explored different beaches where she can swim and play ‘fetch,’ her favorite game and one of the main sources of work and reward (essential for a Labrador) in her life (the larger the stick/stimulus, the better). We’ve traveled on the train together, each week, in our commute from the rural village where I’ve been living to the city of Cagliari, where I was doing research at an Italian university, Nira nestled at my feet on her Italian-made cotton bed, curled into a small ball. We’ve hiked all over our village, greeting sheep, horses and cattle along the way.

Since then, we have been inseparable, and, although not part of the initial plan to have her here with me for the year, doing fieldwork with her in my midst has been much like the narratives I’ve read of doing fieldwork with a child in tow. Each Sunday, we’ve explored different beaches where she can swim and play ‘fetch,’ her favorite game and one of the main sources of work and reward (essential for a Labrador) in her life (the larger the stick/stimulus, the better). We’ve traveled on the train together, each week, in our commute from the rural village where I’ve been living to the city of Cagliari, where I was doing research at an Italian university, Nira nestled at my feet on her Italian-made cotton bed, curled into a small ball. We’ve hiked all over our village, greeting sheep, horses and cattle along the way.

Nira’s presence has also summoned all sorts of perspectives and approaches to social life, to the human-animal interface, and to gender that are precious to me as I continue to learn more about this island, from the space of both the rural and the urban. For example, one of the most common questions I am asked when I am out walking with her in the city of Cagliari when someone is contemplating greeting her, or letting their dog greet her, is: “Femminuccia (Is she a girl)?” This question becomes code for “is she gentle?” and “does she bite?,” with the assumption being that in Sardegna, most male dogs are not neutered, and are thus perceived as being intrinsically territorial, aggressive or wanting to procreate and that, by inversion, female dogs, whether spayed or no, are going to be less aggressive, better behaved and generally more “gentile” (kind, nice, well-behaved). Thus, behavior and comportment become gendered in ways very different than they are in the U.S., where dog behavior is linked more to ideas of a dog’s training and history of aggression and less with its gender per se.

In the rural village where I am living in the Sardinian foothills of the “Montiferru,” responses to Nira’s presence have also been strongly gendered, but in a different way. Men in general have responded positively, often wanting to get closer to her, sometimes pet her, and ask about her “qualifications,” for example, if she is “pure” bred and what kind of work she is bred to do. This is particularly true for the men we’ve met who do agricultural and pastoral work, such as work in the vineyards or those who work as shepherds, a common profession in a place where there are more sheep than people. When they learn she is a bird dog trained for hunting with a very delicate mouth built for fowl retrieval, she is met with approval, some additional pats on her head, comments about her physique, and a certain kind of respect. By contrast, many of the women in the village initially have expressed fear when meeting her, particularly based on her size (she is around 55 pounds, or 25 kilos). In both cases, here in the village dogs are perceived as being outdoor animals, and, my fantastic landlord notwithstanding, there is general incredulity surrounding the idea that a dog can be “house trained” or live inside a building.

But my year in Sardegna would not have been possible without the graces of an amazing dogsitter, who was available to watch Nira each time I needed to leave the island to give a talk, play a show, or, as luck would have it, when I was blocked from re-entering the country during a global pandemic. Denise Valentini, student in Pharmacy studies at the University of Cagliari and her partner, Gabriele, also a University student, ending up taking Nira for the entire nine weeks of the most severe phase of the Italian quarantine, inviting her into their sunny flat in the San Benedetto neighborhood of Cagliari, taking her for walks, and giving Nira her daily dose of peanut butter in her favorite red rubber Kong. Every few days, I would receive a video of Nira’s progress in learning new Italian commands, and showing her generally preferred state of being, i.e. lying in a sunny patch on the floor and taking a sun nap.

I am now lucky to be back on Sardinian soil, the worst part of the pandemic drawing to a close (or so we very much hope) and the lockdown now lifted; Nira has a new paunch, perhaps thanks to her prosciutto-flavored dogfood (the Italian equivalent of bacon: thinly sliced and salted Italian ham) that she was introduced to by Denise and Gabriele, a nod to the prevalence of Italian gastronomy, even in pet food. She is relaxed, happy and seems profoundly unconcerned with the comings and goings of the world during this time of general anxiety and panic. When I picked her up on Sunday, both of us en route to a two week mandatory quarantine, I commented on how impressed I was that she was responding to and learning new commands in Italian such as “shake.” Denise and Gabriele, by contrast, remarked that it was amazing to see how excited she was for peanut butter, and yet how unexcited she was when they put Nutella on their bread . “She is so American,” Gabriele said affectionately. As he said this, I remembered all the times my own preference for peanut butter has been playfully teased and questioned while in Italy, a food that many Italians I know regard as one perhaps step up from eating raw lard. I realized that, in many ways, Nira has been my surrogate throughout this year, an intermediary that gives my much-needed insight—and essential companionship—throughout our year, together. I’ll end by sharing a the recording of the chorus to a brand-new song, my tribute to Nira written with Meredith Wilder, called “Everything in this life I need to know, I learned it from my dog.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed