I have been traveling on my own since I was about fifteen. From the very beginning, there have been things I have especially loved to do while traveling, and other things I have explicitly avoided. I don’t like visiting cathedrals, and I tend to avoid the “greatest hits.” I love finding small, tucked away places, hunkering down and getting to know a new world from another’s perspective in that place. This has remained fairly consistent, for me, over the last twenty eight years (I am now forty three).

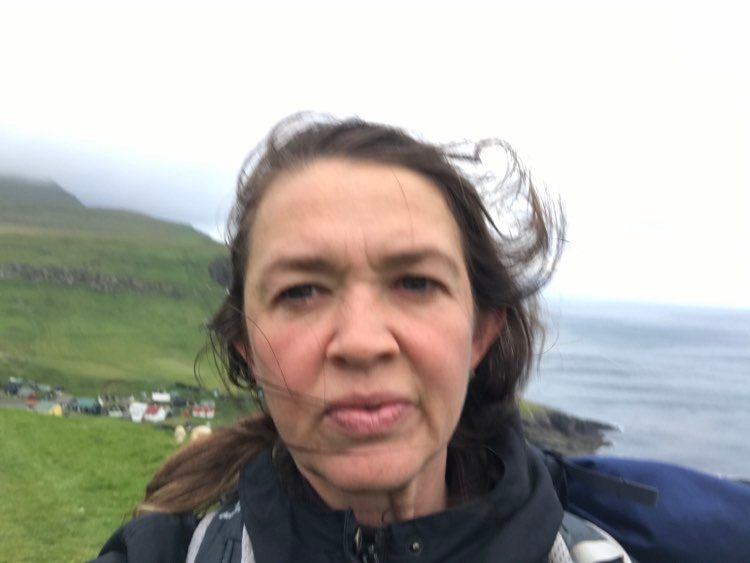

As an ethnographer and songwriter, here are some of the things that, for me and when I travel/expore a new place, help me live more deeply and more fully into my own travel experience and find a sense of connection to place. As I write from my travel trailer in a garden in the capital city of Tórshavn, I realize that many of these early instincts are also best practices in ethnography, in the movement of sustainable travel, in looking for artistic sustenance and inspiration when we travel (what Julia Cameron might call an extended “artist date”), but also in what it means to travel with a light footprint but a full and connected heart. These thoughts are offered not as dictates or moral judgments on how people should travel (we have enough judgment in this world to last us a lifetime!), but in the hopes that they might inspire or incite some of your own ideas and excitement on possibly new, simpler and more sustainable ways to travel and to live into other worlds beyond the ones we already know.

As an ethnographer and songwriter, here are some of the things that, for me and when I travel/expore a new place, help me live more deeply and more fully into my own travel experience and find a sense of connection to place. As I write from my travel trailer in a garden in the capital city of Tórshavn, I realize that many of these early instincts are also best practices in ethnography, in the movement of sustainable travel, in looking for artistic sustenance and inspiration when we travel (what Julia Cameron might call an extended “artist date”), but also in what it means to travel with a light footprint but a full and connected heart. These thoughts are offered not as dictates or moral judgments on how people should travel (we have enough judgment in this world to last us a lifetime!), but in the hopes that they might inspire or incite some of your own ideas and excitement on possibly new, simpler and more sustainable ways to travel and to live into other worlds beyond the ones we already know.

1.Prioritize #one place over many

While the temptation, when we travel, is to try to cover as much ground as possible,

especially in an unknown place, I actually try to do the opposite. Instead, I have found

that hunkering down in one place—a small town, a village, or a place that has at least

one coffee shop and some beautiful natural surroundings and a place to sleep—can reap much richer rewards for becoming connected to a new place. When you stay in the same place and show up repeatedly, people become curious. You become a familiar face, and the bartender, the other people who frequent that place will often become more comfortable reaching out to you, talking to you, sharing their music, their language, their world, and even helping you out in a pinch, should you need it. I think of this as “staying close” and “going deep” rather than “going far.” Going far—encompassing as many towns and cities as possible in a short amount of time—gives us geographic breadth. But staying close gives us human and cultural depth that, typically, can only be gained over a period of days, weeks and even months. This helps to build relationships and give us, while we travel, a sense of groundedness in place.

While the temptation, when we travel, is to try to cover as much ground as possible,

especially in an unknown place, I actually try to do the opposite. Instead, I have found

that hunkering down in one place—a small town, a village, or a place that has at least

one coffee shop and some beautiful natural surroundings and a place to sleep—can reap much richer rewards for becoming connected to a new place. When you stay in the same place and show up repeatedly, people become curious. You become a familiar face, and the bartender, the other people who frequent that place will often become more comfortable reaching out to you, talking to you, sharing their music, their language, their world, and even helping you out in a pinch, should you need it. I think of this as “staying close” and “going deep” rather than “going far.” Going far—encompassing as many towns and cities as possible in a short amount of time—gives us geographic breadth. But staying close gives us human and cultural depth that, typically, can only be gained over a period of days, weeks and even months. This helps to build relationships and give us, while we travel, a sense of groundedness in place.

2.Prioritize #People over Places

This dictum came up for me, just this last Thursday here in Tórshavn, the Faroe Islands. I had made plans with myself to take an elaborate ferry ride to the island of Kalsoy to see the famous Kallurin lighthouse, the site of many scenes in the most recent James Bond movie, on Friday (the next day). It’s stunningly beautiful and, while I don’t like following the beaten path very often, this one included a challenging hike and seemed worth the day-long effort it would take to get there. On Thursday, when I popped into a Faroese music store and recording label called TUTL, the employee mentioned to me that on Friday afternoons, they do a live acoustic music set in the store for passersby. He then noted that the person they had lined up for Friday had just canceled, and said the spot was mine if I wanted to take it. I took an hour to think about it, and, in that time as I journaled, remembered my own “people over places” principal. Playing a show for new people, in a new city, in a new country, in a record store (a type of gig I had never done), would be about human connection and people rather than seeing a new place. And that is often my sweetspot, emotionally and musically speaking. The visit to the lighthouse was, in essence, a placeholder to fill my time until the “real” interactions began. And they were beginning! So I returned, canceled my trip to Kalsoy, agreed to the gig and played it the next day.

It was everything I had hoped it would be: intimate, sweet, and connective. My neighbors from my Airbnb came, as did my songwriter friend, his partner, and their new baby. Passersby dropped in from the walking street, and there were even some folks from Nólsoy, the island where I’d stayed the week before. So, when and if we have the opportunity, if a personal invite to extend dialogue with someone new comes up, prioritize that over the place you were going to go to or the thing you were going to do. One is a placeholder, the the other is the thing you (or at least I) came for! In the moment, this can, sometimes, be easy to forget as we become attached to whatever the original plan might have been.

1.#Stay in Memorable Places (i.e. Avoid the Hotel)

They will stay with you in a way that the hotel room never will! Right now, I am staying

in this travel trailer: it’s raining outside, there’s a little draft coming in through the front door, but there’s a cozy gas heater and a giant skylight. From my skylight, I can see the seagulls, the crows, and my neighbors’ beautiful glass studio, built on the second floor to maximize wintertime sunlight in the Faroes. Last week, I stayed in a “tiny house” on the neighboring island of Nólsoy. It was only a smidge larger than this travel trailer, smelled of fresh pine, had “Danish hygge” candles and an exquisite view of the sea and the town harbor from every angle. It also had no curtains! In this town of 320 people, even when it was cold and rainy, I could watch village life from inside the house and still feel like I was a part of it. Because I was staying in a community and because each of these spaces engaged my attention and intention on so many levels—figuring out where to put things, learning how to take a shower in a small space, buying thumbtacks to put towels on the windows because the sun never sets at this time of year, cooking lots of warm soups to stay warm—I will always remember how I felt in relation to the place I was staying. This, for me, helps to cement not only the experience in my memory, but my experience of the place, as well.

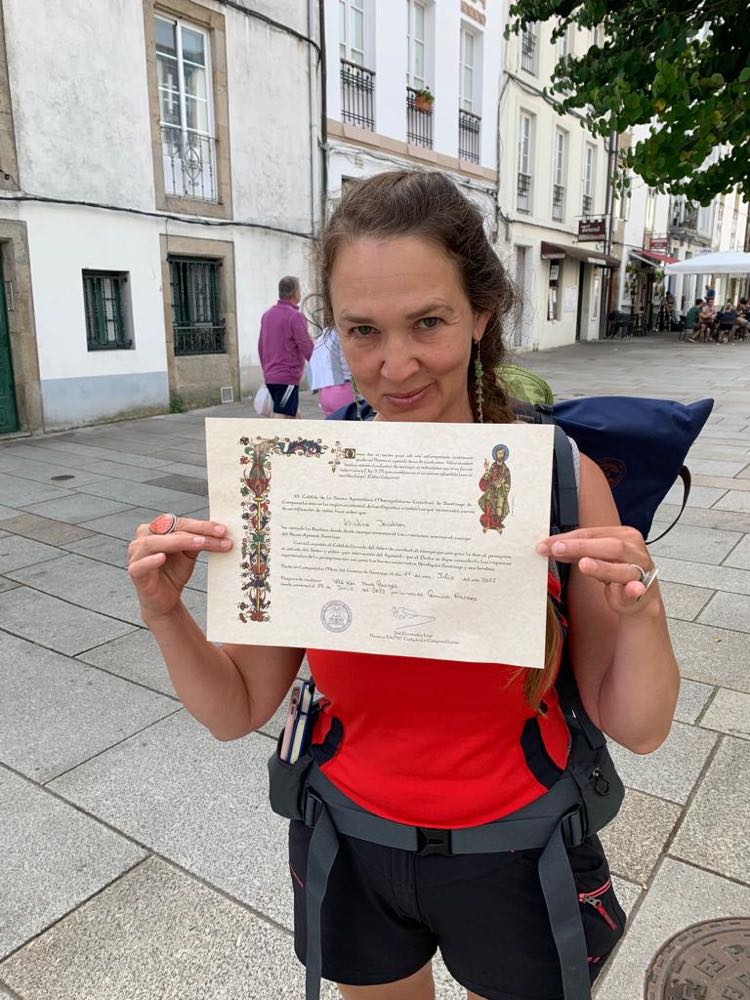

As a different kind of example related to unique places to stay: Walking the Camino de Santiago (Camino Francés) in northern Spain, this summer, we stayed at a different albergue—hostels designed for pilgrims walking the camino—each night. It was a frenzy of different places, for 21 days, where we stayed on cots in co-ed rooms with betweeen 10-60 beds, sometimes with only one 1-2 large, shared bathrooms. While this might sound rather grim, it wasn’t. And there are 3-4 albergues that I can name for you, immediately, that were incredibly beautiful, restful, and, in their own way, even felt private. Some, like the Catholic convent we stayed in, had stunning rest, writing and reflection areas, others, like the albergue owned by an Australian-British expat and her Spanish partner, had delicious, homecooked community meals harvested from her garden, each night, and a cold mountain stream to bathe our sore knees and feet in, under a bridge in the back yard. Still others provided beautiful hammocks, in-house massage therapists for tired backs and feet, or fresh flowers on every surface. Even though we stayed in so many places, these are the ones that will stay in my memory and that made such a difference to this weary traveler!

They will stay with you in a way that the hotel room never will! Right now, I am staying

in this travel trailer: it’s raining outside, there’s a little draft coming in through the front door, but there’s a cozy gas heater and a giant skylight. From my skylight, I can see the seagulls, the crows, and my neighbors’ beautiful glass studio, built on the second floor to maximize wintertime sunlight in the Faroes. Last week, I stayed in a “tiny house” on the neighboring island of Nólsoy. It was only a smidge larger than this travel trailer, smelled of fresh pine, had “Danish hygge” candles and an exquisite view of the sea and the town harbor from every angle. It also had no curtains! In this town of 320 people, even when it was cold and rainy, I could watch village life from inside the house and still feel like I was a part of it. Because I was staying in a community and because each of these spaces engaged my attention and intention on so many levels—figuring out where to put things, learning how to take a shower in a small space, buying thumbtacks to put towels on the windows because the sun never sets at this time of year, cooking lots of warm soups to stay warm—I will always remember how I felt in relation to the place I was staying. This, for me, helps to cement not only the experience in my memory, but my experience of the place, as well.

As a different kind of example related to unique places to stay: Walking the Camino de Santiago (Camino Francés) in northern Spain, this summer, we stayed at a different albergue—hostels designed for pilgrims walking the camino—each night. It was a frenzy of different places, for 21 days, where we stayed on cots in co-ed rooms with betweeen 10-60 beds, sometimes with only one 1-2 large, shared bathrooms. While this might sound rather grim, it wasn’t. And there are 3-4 albergues that I can name for you, immediately, that were incredibly beautiful, restful, and, in their own way, even felt private. Some, like the Catholic convent we stayed in, had stunning rest, writing and reflection areas, others, like the albergue owned by an Australian-British expat and her Spanish partner, had delicious, homecooked community meals harvested from her garden, each night, and a cold mountain stream to bathe our sore knees and feet in, under a bridge in the back yard. Still others provided beautiful hammocks, in-house massage therapists for tired backs and feet, or fresh flowers on every surface. Even though we stayed in so many places, these are the ones that will stay in my memory and that made such a difference to this weary traveler!

4. If you can, #stay for longer and on a smaller budget; avoid the “greatest hits”

If you can afford it and have a job that gives you the flexibility to do so, stay as long as you can, wherever you are going, on a lower budget, rather than trying to pack everything into a shorter amount of time and doing what I call the “greatest hits” approach (e.g., the Vatican in Rome, the Eiffel Tower in France, the tower of Pisa in Pisa). For example, many Airbnb rentals will offer you steep discounts for booking two weeks or a month at a time, making the price more similar to an average monthly rental price (in my case, in the U.S.) rather than the steep prices of a hotel. If you rent a space with a kitchen, you can go to the supermarket, stock up on delicious, local food, and prepare most of your meals at home and still eat like a queen. When you do want to go out to a restaurant, it feels like a real treat, and is much more budget-friendly, overall.

Staying long also allows you to become a different kind of traveler. It allows your to live in a place, not just visit it. As a result, you are, in some ways, less needy and less hungry for immediate answers to your travel questions, because you have time to explore things and answer questions for yourself. This opens up mental space for other kinds of questions and conversations with folks from your host community. For example, I like to alternate days of exploration (going out into the city or countryside, visiting museums, shops, restaurants, concerts) with days of reflection and writing spent at the place I’m staying or at a local café. This allows me to absorb/integrate my experiences more fully into my body and my heart and mind, and build on these in conversation with others, while I am still in-country.

I have a friend from graduate school whose parents, one an artist and the other a

minister, would rent a house for a month in a different country each year, and set up

shop with their kids for the summer, there. The dad would write, the mom would paint,

and the kids were free to explore the town and the countryside. They would, in essence,

seek to “live long” in that place and integrate themselves as much as possible for that month, making sure their kids could walk safely to the stores and cafés and could live independently of their parents if they wanted to.

For folks who aren’t yet committed to a long-term job, there are also some options to explore sustainably living in a place. “Workaway” is one, and WWOOFing (World Wide International Opportunities on Organic Farms) is another; each of these providing lodging and food in exchange for a small amount of work (typically four hours/day, five days/week). For those with a Bachelor’s degree, teaching overseas with an international school or another hiring entity is another option.

If you can afford it and have a job that gives you the flexibility to do so, stay as long as you can, wherever you are going, on a lower budget, rather than trying to pack everything into a shorter amount of time and doing what I call the “greatest hits” approach (e.g., the Vatican in Rome, the Eiffel Tower in France, the tower of Pisa in Pisa). For example, many Airbnb rentals will offer you steep discounts for booking two weeks or a month at a time, making the price more similar to an average monthly rental price (in my case, in the U.S.) rather than the steep prices of a hotel. If you rent a space with a kitchen, you can go to the supermarket, stock up on delicious, local food, and prepare most of your meals at home and still eat like a queen. When you do want to go out to a restaurant, it feels like a real treat, and is much more budget-friendly, overall.

Staying long also allows you to become a different kind of traveler. It allows your to live in a place, not just visit it. As a result, you are, in some ways, less needy and less hungry for immediate answers to your travel questions, because you have time to explore things and answer questions for yourself. This opens up mental space for other kinds of questions and conversations with folks from your host community. For example, I like to alternate days of exploration (going out into the city or countryside, visiting museums, shops, restaurants, concerts) with days of reflection and writing spent at the place I’m staying or at a local café. This allows me to absorb/integrate my experiences more fully into my body and my heart and mind, and build on these in conversation with others, while I am still in-country.

I have a friend from graduate school whose parents, one an artist and the other a

minister, would rent a house for a month in a different country each year, and set up

shop with their kids for the summer, there. The dad would write, the mom would paint,

and the kids were free to explore the town and the countryside. They would, in essence,

seek to “live long” in that place and integrate themselves as much as possible for that month, making sure their kids could walk safely to the stores and cafés and could live independently of their parents if they wanted to.

For folks who aren’t yet committed to a long-term job, there are also some options to explore sustainably living in a place. “Workaway” is one, and WWOOFing (World Wide International Opportunities on Organic Farms) is another; each of these providing lodging and food in exchange for a small amount of work (typically four hours/day, five days/week). For those with a Bachelor’s degree, teaching overseas with an international school or another hiring entity is another option.

5.#Go to Church/Temple/a Mosque, even if you’re not religious

I lived for my first summer on Navajo Nation when I was seventeen, and I went to a

different church each Sunday. Although I am not particularly religious and it was a long

bike ride from my housing at Canyon de Chelly National Monument to each church,

many of these services were held in Navajo and the hymns were sung in Navajo. Attending these services on my own allowed me to slowly become a part of the broader Chinle (Navajo Nation) community. I became a familiar face. And each church was

incredibly different, in vibe, in levels of religious intensity, and in how they regarded me. This gave me exposure to the Navajo language and insight into Diné religious life, and also, in my work later on as an anthropologist and ethnomusicologist, also gave me a much broader, ethnographic sense of contemporary spiritual practices on the Navajo Nation.

When I lived in rural Madison County, North Carolina, in the Appalachian mountains, I went on Sundays to a mountain Baptist church with my friend, Debbie. There, we would sing Delmore Brothers duets for the congregation during the service, and Debbie’s husband, Harlon, would preach and lead people in prayer. He would ask them, each week, what was on their hearts, and congregants would respond with sometimes heartrending stories of financial hardship, personal loss, requests for prayers, and family struggles. There were creek baptisms, the laying on of hands for the unwell, and sometimes foot washings. . In a congregation of 20-30 people, these services were incredibly precious, tender, and open. And there was almost always a delicious potluck afterwards, with some of the best butterbeans, biscuits, fried chicken and blackberry cobbler I’ve ever had. While I am not Baptist, and Debbie and Harlon knew this, these services were incredibly moving and a lifeline to me at that time. Going to church with Debbie and Harlon also introduced me to some of the deepest fears and struggles shared by this community, and also introduced me to foodways I might not otherwise ever have tasted. They healed something in me I didn’t know at the time needed healing, and they did this in community, which is one of the most fundamental things I think we need as human beings: to be seen (and loved) for who we are by others in a communal setting.

6. Focus on the Senses

A lifecoach who works with people experiencing complex trauma shared with me

that, to truly “arrive” in a new place, it can help to focus on one of our five (or

six or seven, depending on how you define them) senses, each day. To tune into taste

on day

one, touch on day two, sound on day three, etc. By the time you’ve gone through each

sense, you’ve really arrived in that new place with your full self. I love this and, based on

her suggestion, incorporated some of this

into the mindfulness walks I led each morning for the place-based songwriting workshop

I taught in Sardinia, this summer. I also find that, when I arrive in a new place, my senses are on fire: they are doing overtime, and that is often why I am so tired in the first couple of days. Another technique I’ll engage when I arrive in a new place is to do “object writing,” or writing for eight minutes about an object within your field of vision, again diving deeply into the senses.

The senses, especially when we are attuned to them, become receptacles of memory and of feeling. They allow us to dip into an experience, even one from many years ago, almost instantly. It’s like hearing the song on the radio that instantly transports us back in time; even now, hearing Sting’s “fields of gold” transports me almost instantly back to seventh grade and sitting with my sister in her red VW golf as we listened to this song in our driveway, on a Berkshire summer night in western Massachusetts. Our senses hold our stories.

7.Crafting/Making Something with Your Hands/Making Art

If you can, make something with your hands while you are traveling. This could be a sketch, a song, or working with someone to learn a local craft or foodway. What you make or craft can also be very small-scale and lightweight: when I walked the Camino de Santiago this summer, and when I flew to the Faroe Islands, I walked with a ¼ lb. soprano ukulele, and I would write a line or two between each town as we walked, tweaking the songs later in the day once we’d finally checked into the albergue for the night. This is how I wrote the song, “Living Life at Three Miles an Hour,” recorded with my ukulele, here. In situ songwriting is something I find very powerful: I have written songs on giant rocks in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, on ferries in the Faroes, in crypts in Sardinia, in roundpens on the Navajo Nation, on a canal in Finland, on haybales in western Massachusetts, on old marble stairs below in a castle, and in a pasture on the camino de Santiago, as the cows looked on.

Movement, like art and craft, also sutures us to place, as does artmaking in place. Engage your body in meaningful work of some kind, whether harvesting vegetables, stomping on grapes during the “vendemmia,” harvesting olives, going for hikes, or walking around new neighborhoods. Again, this involves the senses, and each time you repeat this activity, in future, it will allow you to remember where you made the sketch, wrote the song, or learned how to cook that special dish or weave that basket.

Last night (7/24/22), I traveled on a small open boat from the island of Vagar to the neighboring island of Mykines to see the legendary puffin colonies on that island. We put on massive insulated wetsuits. As we headed out to sea, it became stormy, and the waves started crashing over our small boat. Our heads were drenched in seawater, as was my ukulele, my journal, and my backpack. By the time we arrived thirty minutes later to Mykines, we felt like we had truly been through something together. We then climbed up on the steepest mountainsides I’ve ever climbed, and lying down on the top of a cliff, in our wetsuits, to look down the other stide and observe the baby black-and-white pufflings in their nests. On the way back, we all sang rounds together on the boat, feeling like old friends. My body, my senses and my artist’s mind had all been fully engaged, as had a sense of full adventure and newness.

I lived for my first summer on Navajo Nation when I was seventeen, and I went to a

different church each Sunday. Although I am not particularly religious and it was a long

bike ride from my housing at Canyon de Chelly National Monument to each church,

many of these services were held in Navajo and the hymns were sung in Navajo. Attending these services on my own allowed me to slowly become a part of the broader Chinle (Navajo Nation) community. I became a familiar face. And each church was

incredibly different, in vibe, in levels of religious intensity, and in how they regarded me. This gave me exposure to the Navajo language and insight into Diné religious life, and also, in my work later on as an anthropologist and ethnomusicologist, also gave me a much broader, ethnographic sense of contemporary spiritual practices on the Navajo Nation.

When I lived in rural Madison County, North Carolina, in the Appalachian mountains, I went on Sundays to a mountain Baptist church with my friend, Debbie. There, we would sing Delmore Brothers duets for the congregation during the service, and Debbie’s husband, Harlon, would preach and lead people in prayer. He would ask them, each week, what was on their hearts, and congregants would respond with sometimes heartrending stories of financial hardship, personal loss, requests for prayers, and family struggles. There were creek baptisms, the laying on of hands for the unwell, and sometimes foot washings. . In a congregation of 20-30 people, these services were incredibly precious, tender, and open. And there was almost always a delicious potluck afterwards, with some of the best butterbeans, biscuits, fried chicken and blackberry cobbler I’ve ever had. While I am not Baptist, and Debbie and Harlon knew this, these services were incredibly moving and a lifeline to me at that time. Going to church with Debbie and Harlon also introduced me to some of the deepest fears and struggles shared by this community, and also introduced me to foodways I might not otherwise ever have tasted. They healed something in me I didn’t know at the time needed healing, and they did this in community, which is one of the most fundamental things I think we need as human beings: to be seen (and loved) for who we are by others in a communal setting.

6. Focus on the Senses

A lifecoach who works with people experiencing complex trauma shared with me

that, to truly “arrive” in a new place, it can help to focus on one of our five (or

six or seven, depending on how you define them) senses, each day. To tune into taste

on day

one, touch on day two, sound on day three, etc. By the time you’ve gone through each

sense, you’ve really arrived in that new place with your full self. I love this and, based on

her suggestion, incorporated some of this

into the mindfulness walks I led each morning for the place-based songwriting workshop

I taught in Sardinia, this summer. I also find that, when I arrive in a new place, my senses are on fire: they are doing overtime, and that is often why I am so tired in the first couple of days. Another technique I’ll engage when I arrive in a new place is to do “object writing,” or writing for eight minutes about an object within your field of vision, again diving deeply into the senses.

The senses, especially when we are attuned to them, become receptacles of memory and of feeling. They allow us to dip into an experience, even one from many years ago, almost instantly. It’s like hearing the song on the radio that instantly transports us back in time; even now, hearing Sting’s “fields of gold” transports me almost instantly back to seventh grade and sitting with my sister in her red VW golf as we listened to this song in our driveway, on a Berkshire summer night in western Massachusetts. Our senses hold our stories.

7.Crafting/Making Something with Your Hands/Making Art

If you can, make something with your hands while you are traveling. This could be a sketch, a song, or working with someone to learn a local craft or foodway. What you make or craft can also be very small-scale and lightweight: when I walked the Camino de Santiago this summer, and when I flew to the Faroe Islands, I walked with a ¼ lb. soprano ukulele, and I would write a line or two between each town as we walked, tweaking the songs later in the day once we’d finally checked into the albergue for the night. This is how I wrote the song, “Living Life at Three Miles an Hour,” recorded with my ukulele, here. In situ songwriting is something I find very powerful: I have written songs on giant rocks in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, on ferries in the Faroes, in crypts in Sardinia, in roundpens on the Navajo Nation, on a canal in Finland, on haybales in western Massachusetts, on old marble stairs below in a castle, and in a pasture on the camino de Santiago, as the cows looked on.

Movement, like art and craft, also sutures us to place, as does artmaking in place. Engage your body in meaningful work of some kind, whether harvesting vegetables, stomping on grapes during the “vendemmia,” harvesting olives, going for hikes, or walking around new neighborhoods. Again, this involves the senses, and each time you repeat this activity, in future, it will allow you to remember where you made the sketch, wrote the song, or learned how to cook that special dish or weave that basket.

Last night (7/24/22), I traveled on a small open boat from the island of Vagar to the neighboring island of Mykines to see the legendary puffin colonies on that island. We put on massive insulated wetsuits. As we headed out to sea, it became stormy, and the waves started crashing over our small boat. Our heads were drenched in seawater, as was my ukulele, my journal, and my backpack. By the time we arrived thirty minutes later to Mykines, we felt like we had truly been through something together. We then climbed up on the steepest mountainsides I’ve ever climbed, and lying down on the top of a cliff, in our wetsuits, to look down the other stide and observe the baby black-and-white pufflings in their nests. On the way back, we all sang rounds together on the boat, feeling like old friends. My body, my senses and my artist’s mind had all been fully engaged, as had a sense of full adventure and newness.

8.Sit/Write/Observe Life in a Café/Coffee Shop/Teahouse/Shared Public Space

Bringing a journal and sitting/observing the world around me is one of my favorite things to do when I arrive in a new place, and something I do

as frequently as I can (I am doing exactly this from a public library in Tórshavn with

fuzzy sheepskins on the chairs as I write this section!). Sitting in a variety of public spaces allows me to get a sense of the pulse of a place, to see what people are ordering most frequently, how they are ordering it/speaking, what languages and registers of speech they are using with another, and to observe things like body language, body proximity between one person and another, gender dynamics, and so much more. It also, per 6), allows me to tune into my senses, slowly, once sense at a time. Another way I love to do this is through writing old-school, handwritten letters to friends, family and loved ones back home or living in Italy and Denmark.

9. Ways of Getting There: Trains, Ferries, Buses, Walking, Biking, or horse, donkey or camel

As I write this section from an underground sea tunnel, where I am on a public bus on

the Faroes heading to the town of Sørvágur, I am surrounded by Danes and Norwegians, with backpacks and dressed in hiking gear and wool sweaters, heading back to the airport after their days in the Faroes. Out the window, there are fjords, waterfalls traipsing down each mountain, thatch-roofed houses, and sheep grazing almost everywhere. As I ride this bus, I feel, in some small way, like I am becoming a part of this place.

The other main form of transport in the Faroes is the ferry, a form of transportation I love (ferries and helicopters are the cheapest forms of public transport in the Faroes). Furnished with a warm indoor observation deck and a coffee machine, ferries are the perfect place for journaling and writing letters. For my own next big journey, perhaps in South Asia, I’d love to travel exclusively via train and walking.

How we get there matters. As I expressed in a cowrite with John Parish, oftentimes I feel that “The Medium is the Message.” And, although I too am dependent on flying when traveling from the U.S. to many places, I find there is a certain violence and suddenness to flying--leaving one place and ending up in a drastically new one, with very little transition time--that slower forms of travel help to mitigate.

11.Local Media: Reading the newspaper, listening to the radio/watch television

What are the current issues affecting the place you’ve arrived in? What is important to

the people around you in this new place? How does it connect back to the things

that interest you in that place? Even if you don’t read the language of the place you are in, can you google enough to get the gist? Or can you find a version of that country’s news in a language (or a podcast) you do speak or read?

My first summer living in Sardinia, Italy, I would read the two main newspapers on the

island, almost daily, at the bar around the corner from my house. “La Nuova” and “L’Unione Sarda” are different papers, politically, that focus on different aspects of Sardinian life, so that was important to glean from comparing the two. I read about sheepherders and dairy collectives going on strike, about regional politics, and about Italy’s ongoing financial crisis.

On the Navajo Nation, The Navajo Times comes out each Thursday. Living on an isolated mesa with no running water, I would religiously read the OpEds (opinion section) of the Times; it was my essential weekly reading to get a pulse for issues that were close to my neighbors and extended family members’ hearts.

Similarly, if you can get a local station either on the radio dial or via streaming, try

tuning in. What music is being played, what language is being spoken? What matters to people, based on what you can glean from what you’ve

listened to?

12. What would you add?

Last but not least, dear reader: what would you add to this list, based on your own lived experience? What skillsets do you like to engage in specifically when you travel, whether that’s in your hometown on a “staycation” or an extended trip overseas?

I welcome your feedback, thoughts and responses.

Bringing a journal and sitting/observing the world around me is one of my favorite things to do when I arrive in a new place, and something I do

as frequently as I can (I am doing exactly this from a public library in Tórshavn with

fuzzy sheepskins on the chairs as I write this section!). Sitting in a variety of public spaces allows me to get a sense of the pulse of a place, to see what people are ordering most frequently, how they are ordering it/speaking, what languages and registers of speech they are using with another, and to observe things like body language, body proximity between one person and another, gender dynamics, and so much more. It also, per 6), allows me to tune into my senses, slowly, once sense at a time. Another way I love to do this is through writing old-school, handwritten letters to friends, family and loved ones back home or living in Italy and Denmark.

9. Ways of Getting There: Trains, Ferries, Buses, Walking, Biking, or horse, donkey or camel

As I write this section from an underground sea tunnel, where I am on a public bus on

the Faroes heading to the town of Sørvágur, I am surrounded by Danes and Norwegians, with backpacks and dressed in hiking gear and wool sweaters, heading back to the airport after their days in the Faroes. Out the window, there are fjords, waterfalls traipsing down each mountain, thatch-roofed houses, and sheep grazing almost everywhere. As I ride this bus, I feel, in some small way, like I am becoming a part of this place.

The other main form of transport in the Faroes is the ferry, a form of transportation I love (ferries and helicopters are the cheapest forms of public transport in the Faroes). Furnished with a warm indoor observation deck and a coffee machine, ferries are the perfect place for journaling and writing letters. For my own next big journey, perhaps in South Asia, I’d love to travel exclusively via train and walking.

How we get there matters. As I expressed in a cowrite with John Parish, oftentimes I feel that “The Medium is the Message.” And, although I too am dependent on flying when traveling from the U.S. to many places, I find there is a certain violence and suddenness to flying--leaving one place and ending up in a drastically new one, with very little transition time--that slower forms of travel help to mitigate.

11.Local Media: Reading the newspaper, listening to the radio/watch television

What are the current issues affecting the place you’ve arrived in? What is important to

the people around you in this new place? How does it connect back to the things

that interest you in that place? Even if you don’t read the language of the place you are in, can you google enough to get the gist? Or can you find a version of that country’s news in a language (or a podcast) you do speak or read?

My first summer living in Sardinia, Italy, I would read the two main newspapers on the

island, almost daily, at the bar around the corner from my house. “La Nuova” and “L’Unione Sarda” are different papers, politically, that focus on different aspects of Sardinian life, so that was important to glean from comparing the two. I read about sheepherders and dairy collectives going on strike, about regional politics, and about Italy’s ongoing financial crisis.

On the Navajo Nation, The Navajo Times comes out each Thursday. Living on an isolated mesa with no running water, I would religiously read the OpEds (opinion section) of the Times; it was my essential weekly reading to get a pulse for issues that were close to my neighbors and extended family members’ hearts.

Similarly, if you can get a local station either on the radio dial or via streaming, try

tuning in. What music is being played, what language is being spoken? What matters to people, based on what you can glean from what you’ve

listened to?

12. What would you add?

Last but not least, dear reader: what would you add to this list, based on your own lived experience? What skillsets do you like to engage in specifically when you travel, whether that’s in your hometown on a “staycation” or an extended trip overseas?

I welcome your feedback, thoughts and responses.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed