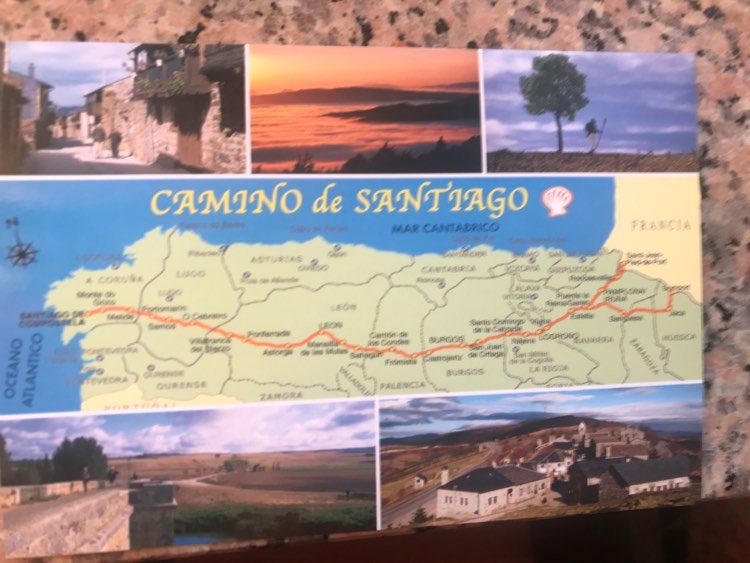

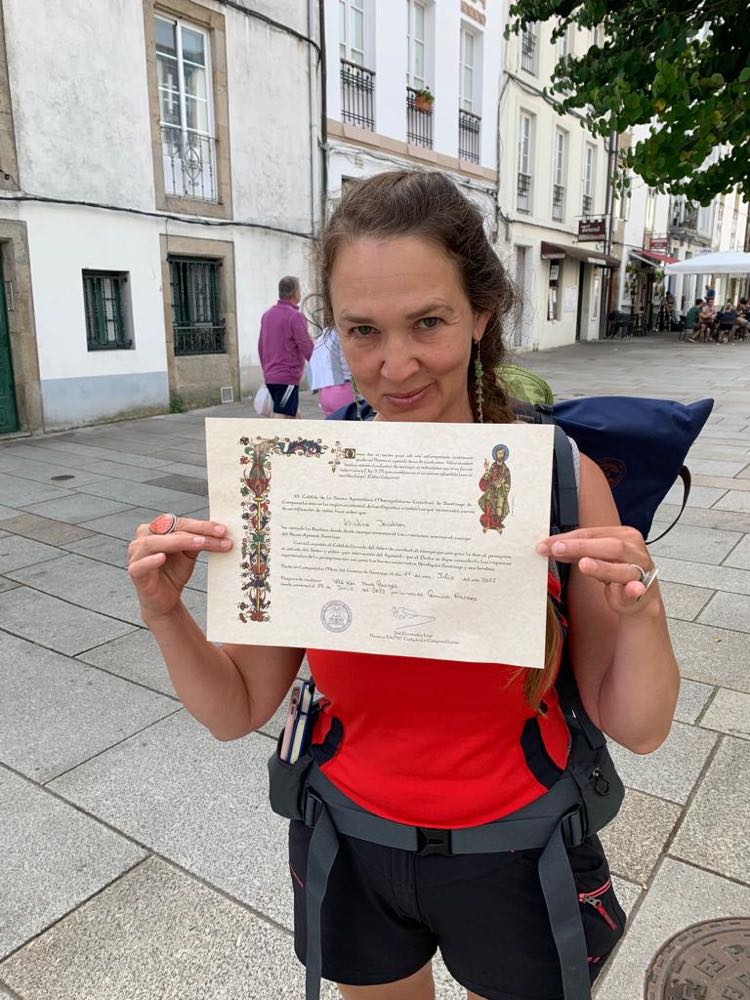

I left for the Camino de Santiago (Camino Francés) from Burgos on June 20th, and ended in Santiago de Compostela on July 12.th While my Compostela (certificate of completion) says I completed 490 kilometers, of which I walked about 450 (ca. 279 miles). As I write from the Madrid airport and now from the Faroe Islands, after moving through the world walking at three miles/4 kilometers an hour for almost three weeks, I realize how much culture shock I am still going through as I retransition to cars, the big city, and a very different pace of life.

After following the guidebook for the first week or so, we realized that, based on the number of people also following the same guidebook from across Europe, Australia, New Zealand and the U.S., that we could cultivate more intimate and less crowded camino experiences if we intentioanlly decided to stay at the “tapas” (stops) that were in between the principle stops recommended in the guidebook. This opened up all sorts of new possibilities! We also downloaded some new phone apps (“buen camino” and “gronze”) that allowed us to research our respective “albergues” (hostels) in each town with a finer toothed comb and to find ones that specialized in local, unique experiences with smaller rooms and fewer people, overall (albergues range from 10-80 people). We then reserved these one day in advance, on the phone. This steered us to very small, rural towns, with one or two albergues, where dinner and breakfast was often offered directly at the albergue. Dinners were often a “cena comunitaria” (community dinner), where all the pilgrims and our host sat and ate together. This helped create the sort of more personal and intimate experience we were hoping to cultivate on the camino immensely, and also allowed us to meet other people that were, like us, perhaps more introverted and wanting to stay in the inbetween spots. For this reason, together with our friends Peter (the Netherlands) and Henrik (Denmark), we started calling ourselves the “inbetweeners.”

As the saying goes, each person walks their own camino, and so part of the journey was us trying to find our own. We found that the right pace for us was between 20-25 kilometers (roughly 12-15 miles) per day, walking at about four kilometers (roughly three miles) an hour, depending on terrain and steepness. Leaving between 6-7 a.m., this allowed us to arrive at our destination after roughly 5-6 hours of walking with 1-2 short stops for coffee and snacks, or by around 2 p.m. each afternoon. After a long nap and some lunch, in this way we still had some energy to walk around, write songs, journal, and explore the town through its food, wines and walking.

I also feel somewhat conflicted about my first camino experience. We had both watched the movie The Way, and so I am sure that some of my own expectations were colored by the film, which is a sort of an epic, road-trip style walking tour through northern Spain for a bunch of eclectic travelers, each trying to resolve some major issue in their lives. So part of my work was letting go over those expectations and leaning into what was the actual experience presented to me, day by day, moment by moment.

What I loved: I *loved* walking everyday, traveling slowly, and exploring the small, rural towns of northern Spain on foot. I loved knowing that, at each village we stopped at, there was a reasonable chance of finding a good Spanish tortilla and a café con leche. What an incredible way to travel! I would love to travel a good part of the world this way, on foot, or a mix of on foot or on train. Besides the high environmental impacts, there is a violence to flying—the rapidity, the leaving one place and miraculously showing up in another—that traveling on foot and by train responds to elegantly and with intention and care. I love this.

And there is growing evidence that the camino is helping to significantly economically revitalize small towns across Spain, particularly after the pandemic. We also made some exquisite friends, many of whom we hope to visit across Europe, next year. Since you are stripped down to your essence on the camino, there is very little posturing; the camino cultivates an authenticity of conversation and connection that is hard to find in other ambits of our lives.

What I felt more conflicted about: On the other hand, around 250,000 people walk the Camino Francés, specifically, each year, and the sheer number of pilgrims can feel overwhelming. In the towns of only 30-40 residents (there were many), the number of pilgrims massively outran the number of town residents, making it feel more like a noisy summer camp than a pilgrimage. In this sense, my camino experience felt like a mix of part piligrimage, part college Spring Break. This was particularly evident at the bars where, after a particularly long stretch of nothing, folks would congregate to celebrate and get ready for the next leg of the walk. The numbers also present other issues: there is a huge amount of toilet paper left along the trails, where hikers go to the bathroom and don’t pack out, and in larger towns there seems to be a version of “pilgrim fatigue,” where albergues, grocery stores and businesses were simply tired (and sometimes suspicious) of accommodating weary hikers who needed to rest, wash their clothers, bathe and feed their bodies. So, for better and for worse, our own participation in the camino also added to this dynamic.

As teachers, we were also struck by the economic viability of this mode of travel. The prices for albergues remained phenomenally low throughout the trip, between 10-15 euros/person. This included a bed, access to a bathroom and all albergue facilities. In each town along the camino, restaurants offer pre-fixe “pilgrims meals,” where, for between 10-15 euros, you can eat a three course meal and have local wine, coffee and desert. While the quality of the food varied greatly (some were phenomenal, some were mediocre), you were assured that you would eat and have enough to eat. When we did the math, we realized we might have spent less on the camino than we would have spent staying in our hometown of Albuquerque, for the month!

It is super easy to compare yourself to others on the camino! We met marathon runners who were running the camino, with a cart behind them, running 50-60 kilometers (30-40 miles) a day. We met a woman from Germany who had walked from her doorstep in Hanover, Germany, pulling a handmade cart strapped to her hip, and was planning to walk all the way back to Hanover. We saw people walking the camino with walkers, in nonmechanized wheelchairs, and people who are blind, using only their probing cane to guide them along the bumpy terrain. We also met a man from Ireland who was getting ready to assist a pilgrim with cerebral palsy, doing the camino in a wheelchair, complete his land two weeks of the camino. (with the help of a massive support team, he had been been doing one week of the camino, each year, for the past three years before COVID). Our friend Henrik met a man who had been diagnosed with brain cancer and was dying; he was walking eight kilometers a day.

I also feel somewhat conflicted about my first camino experience. We had both watched the movie The Way, and so I am sure that some of my own expectations were colored by the film, which is a sort of an epic, road-trip style walking tour through northern Spain for a bunch of eclectic travelers, each trying to resolve some major issue in their lives. So part of my work was letting go over those expectations and leaning into what was the actual experience presented to me, day by day, moment by moment.

What I loved: I *loved* walking everyday, traveling slowly, and exploring the small, rural towns of northern Spain on foot. I loved knowing that, at each village we stopped at, there was a reasonable chance of finding a good Spanish tortilla and a café con leche. What an incredible way to travel! I would love to travel a good part of the world this way, on foot, or a mix of on foot or on train. Besides the high environmental impacts, there is a violence to flying—the rapidity, the leaving one place and miraculously showing up in another—that traveling on foot and by train responds to elegantly and with intention and care. I love this.

And there is growing evidence that the camino is helping to significantly economically revitalize small towns across Spain, particularly after the pandemic. We also made some exquisite friends, many of whom we hope to visit across Europe, next year. Since you are stripped down to your essence on the camino, there is very little posturing; the camino cultivates an authenticity of conversation and connection that is hard to find in other ambits of our lives.

What I felt more conflicted about: On the other hand, around 250,000 people walk the Camino Francés, specifically, each year, and the sheer number of pilgrims can feel overwhelming. In the towns of only 30-40 residents (there were many), the number of pilgrims massively outran the number of town residents, making it feel more like a noisy summer camp than a pilgrimage. In this sense, my camino experience felt like a mix of part piligrimage, part college Spring Break. This was particularly evident at the bars where, after a particularly long stretch of nothing, folks would congregate to celebrate and get ready for the next leg of the walk. The numbers also present other issues: there is a huge amount of toilet paper left along the trails, where hikers go to the bathroom and don’t pack out, and in larger towns there seems to be a version of “pilgrim fatigue,” where albergues, grocery stores and businesses were simply tired (and sometimes suspicious) of accommodating weary hikers who needed to rest, wash their clothers, bathe and feed their bodies. So, for better and for worse, our own participation in the camino also added to this dynamic.

As teachers, we were also struck by the economic viability of this mode of travel. The prices for albergues remained phenomenally low throughout the trip, between 10-15 euros/person. This included a bed, access to a bathroom and all albergue facilities. In each town along the camino, restaurants offer pre-fixe “pilgrims meals,” where, for between 10-15 euros, you can eat a three course meal and have local wine, coffee and desert. While the quality of the food varied greatly (some were phenomenal, some were mediocre), you were assured that you would eat and have enough to eat. When we did the math, we realized we might have spent less on the camino than we would have spent staying in our hometown of Albuquerque, for the month!

It is super easy to compare yourself to others on the camino! We met marathon runners who were running the camino, with a cart behind them, running 50-60 kilometers (30-40 miles) a day. We met a woman from Germany who had walked from her doorstep in Hanover, Germany, pulling a handmade cart strapped to her hip, and was planning to walk all the way back to Hanover. We saw people walking the camino with walkers, in nonmechanized wheelchairs, and people who are blind, using only their probing cane to guide them along the bumpy terrain. We also met a man from Ireland who was getting ready to assist a pilgrim with cerebral palsy, doing the camino in a wheelchair, complete his land two weeks of the camino. (with the help of a massive support team, he had been been doing one week of the camino, each year, for the past three years before COVID). Our friend Henrik met a man who had been diagnosed with brain cancer and was dying; he was walking eight kilometers a day.

As I step back and reflect on some of the larger takeaways, one of the things that blew me away, coming from a U.S. perspective, is the respect afforded to walkers of the camino in Spain. On our very first morning, leaving from our hostel together in Burgos, a man running by us in the park said to us both, “buen camino.” It was a recognition that we were on pilgrimage, together, that he saw that, and that he wished us well. It felt amazing. This greeting became the norm throughout the walk, where older Spanish men and women in particular would go out of their way to wish us a “buen camino” and point us in the right direction if we were lost. In one instance, an older woman on the second story of her house opened her shutters and yelled down to us and our friends, “buen camino!” It’s also a greeting that many pilgrims on the camino now use with one another.

Many of the Spaniards we met do a small piece of the camino, each year. Many walk for the week leading up to Holy Week, before Easter. High School and College students are sometimes required to complete a week of walking together on the camino, as a sort of group bonding before embarking on learning, together. And anyone that has walked the camino puts it on their CV, and it is considered a mark of one’s integrity and ability to successfully follow through on a given task.

Spain also funds medical assistance to camino walkers through the Guardia Civil. One morning, on a particularly long and hot 17 km stretch before our first break, they slowly drove up and down the camino path, checking to see if anyone needed medical assistance, bandaging for blisters (the primary issue for hikers, epsecially in the first week) or transport to a medical facility. Other times, they stopped us to recommend a safer walking route off the main road or to monitor safe pedestrian crossing of busy highways. Other times, they were on horseback. In the most dramatic instance, when a close friend we were walking with had a seizure on the camino, they showed up to offer basic medical assistance until the ambulance arrived. When this friend was treated on-location in the ambulance so that he could continue walking (this was his request), all medical services were covered and were completely free.

So, hikers are respected and the recognition of undertaking the camino is not only accepted and acknowledged, it is lauded, supported and admired. And it has name recognition. Even at the airport this morning, when I went through security, a security guard recognized the telltale white shell with the red cross on the outside of my backpack and asked me if I had done the “camino.” I said yes, and she smiled and nodded her head approvingly. It reminded me of re-entering the U.S. after having completed my Fulbright year in Italy, when the customs agent knew about the Fulbright and fastracked my paperwork upon my return into my home country.

I grew up along the Appalachian Trail in western Massachusetts, and I have vague memories of hikers coming into the back yard and asking my parents for a hose to fill their water bottles and cool off during the Berkshire summer heat. I also recall, when I lived in Hot Springs, North Carolina, that there was an active AT “through hiker” presence, and you would see backpacks on the sidewalk while hikers went into the local stores to purchase supplies. So I recall the presence of hiker-pilgrims, in some sense, in my life in the U.S. But I am keenly aware that hikers, and people living out of packs for months at a time, might also just as easily be read by an American public not as pilgrims worthy of respect, but as unsheltered and unemployed, and including all of the stigma that comes with these assignations. In other words, in a U.S. context, I think that the desire to travel on foot might more often than not get read not as a choice, but because there is no other option open to that person.

Many of the Spaniards we met do a small piece of the camino, each year. Many walk for the week leading up to Holy Week, before Easter. High School and College students are sometimes required to complete a week of walking together on the camino, as a sort of group bonding before embarking on learning, together. And anyone that has walked the camino puts it on their CV, and it is considered a mark of one’s integrity and ability to successfully follow through on a given task.

Spain also funds medical assistance to camino walkers through the Guardia Civil. One morning, on a particularly long and hot 17 km stretch before our first break, they slowly drove up and down the camino path, checking to see if anyone needed medical assistance, bandaging for blisters (the primary issue for hikers, epsecially in the first week) or transport to a medical facility. Other times, they stopped us to recommend a safer walking route off the main road or to monitor safe pedestrian crossing of busy highways. Other times, they were on horseback. In the most dramatic instance, when a close friend we were walking with had a seizure on the camino, they showed up to offer basic medical assistance until the ambulance arrived. When this friend was treated on-location in the ambulance so that he could continue walking (this was his request), all medical services were covered and were completely free.

So, hikers are respected and the recognition of undertaking the camino is not only accepted and acknowledged, it is lauded, supported and admired. And it has name recognition. Even at the airport this morning, when I went through security, a security guard recognized the telltale white shell with the red cross on the outside of my backpack and asked me if I had done the “camino.” I said yes, and she smiled and nodded her head approvingly. It reminded me of re-entering the U.S. after having completed my Fulbright year in Italy, when the customs agent knew about the Fulbright and fastracked my paperwork upon my return into my home country.

I grew up along the Appalachian Trail in western Massachusetts, and I have vague memories of hikers coming into the back yard and asking my parents for a hose to fill their water bottles and cool off during the Berkshire summer heat. I also recall, when I lived in Hot Springs, North Carolina, that there was an active AT “through hiker” presence, and you would see backpacks on the sidewalk while hikers went into the local stores to purchase supplies. So I recall the presence of hiker-pilgrims, in some sense, in my life in the U.S. But I am keenly aware that hikers, and people living out of packs for months at a time, might also just as easily be read by an American public not as pilgrims worthy of respect, but as unsheltered and unemployed, and including all of the stigma that comes with these assignations. In other words, in a U.S. context, I think that the desire to travel on foot might more often than not get read not as a choice, but because there is no other option open to that person.

What’s next? Is there another camino in the offing? We are not sure. We met many people who have walked the camino francés four, five and six times, and call themselves “camino addicts.” I don’t think I’d walk the Camino Francés again, just because there are so many other caminos to walk! There are ones leading to Rome, to Santiago, and even to Jerusalem! While the religious element of the journey is less compelling to us, we are drawn to these lesser walked ones: the camino del norte and the camino primitivo, both also in Spain, and the Camino Portugues, in Portugal. These is also the Camino Francigena, which begins in England and ends in the southern heel of Italy, in Puglia. I for one am tempted to walk through Italy’s south—Calabria, Basilicata and Puglia in particular—perhaps beginning in Rome and then heading south from there, on foot! I know I would come to know southern Italy, its food, its music, its speech, in a visceral and palpable way. Maybe some day!

~I am grateful beyond measure to my partner, John, for inviting me to join him for this journey, which he had started some weeks before, in France (St. Jean). It was the privilege of a lifetime to walk the camino with him.~

RSS Feed

RSS Feed